Over 30 years ago, the Graduate Students’ Association at the University of Alberta in Edmonton began department-level food collection and distribution as a response to high tuition and fees for international students.

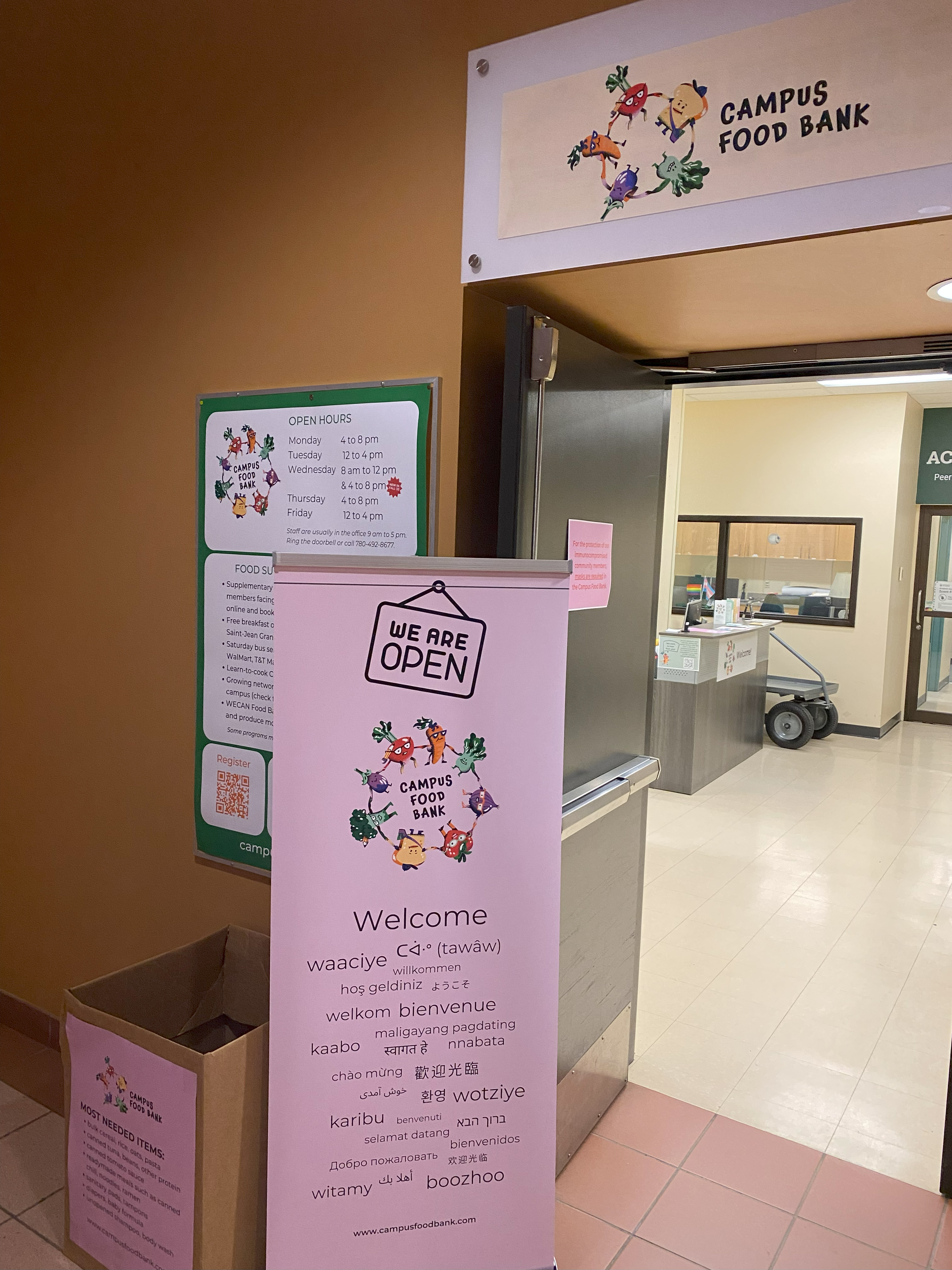

The demand for emergency food assistance was so great that the Campus Food Bank was founded in 1991, turning what was supposed to be a one-time event into the oldest food bank on a university campus in Canada.

“There were students from all backgrounds – including both domestic and international students – lined up out the door,” Campus Food Bank Programs Manager Madi Corry said. “That’s why we became more permanent, because it was clear that a one-time thing was not going to cover it.”

Today, the Campus Food Bank provides supplementary food programming to students and staff, their dependents, and recent alumni as part of their mission to work and advocate for a UofA where everyone has access to food and food education. But according to Corry, staff and volunteers have never been more concerned about managing soaring demand.

In the last HungerCount, which is Food Banks Canada’s signature report documenting food bank use in Canada, the Campus Food Bank recorded more than 400 client visits in March 2022 alone.

“Then, March 2023 just blew that out of the water,” Corry said. “We had 1,052 visits, which means we received more than 1,000 visits in one month for the first time ever.”

A recent survey conducted by the Campus Food Bank in spring 2023 showed that approximately 70 per cent of its clients are international students, who commonly face the challenges of currency fluctuations and restrictions on off-campus employment.

“These students are having to live so far away from campus in order to be able to afford housing,” Campus Food Bank Executive Director Erin O’Neil said. “The bottom line is that their tuition is exorbitant compared to our domestic students.”

On average, Campus Food Bank usage in the 2022–23 school year was 140 per cent higher than in 2021–22.

Summer 2023 has also been their busiest summer ever by far, with more than 15 new client registrations a week in the month of August.

“We’re concerned about managing demand if this trend continues in the coming years,” Corry said. “We’re expecting this September to be more visits than we’ve ever seen.”

‘Hunger for knowledge, not for food’

To help prepare for what is set to be another record fall, Corry said the Campus Food Bank is making programming adjustments that include expanding opening hours to increase the number of clients they can serve.

Embracing a ‘grocery-store’ model of providing food assistance as of November 2022, where visitors browse the food bank shelves and choose foods that will meet their specific cultural and dietary needs, has also improved client dignity, improved the efficiency of the food bank, and reduced food waste.

“It used to take many volunteer hours to assemble pre-packaged food hampers for clients, and we were getting too busy to build hampers for each day,” Corry said. “Now with the grocery model, people are only taking things they need, and we’re not giving them things they might not be able to use.”

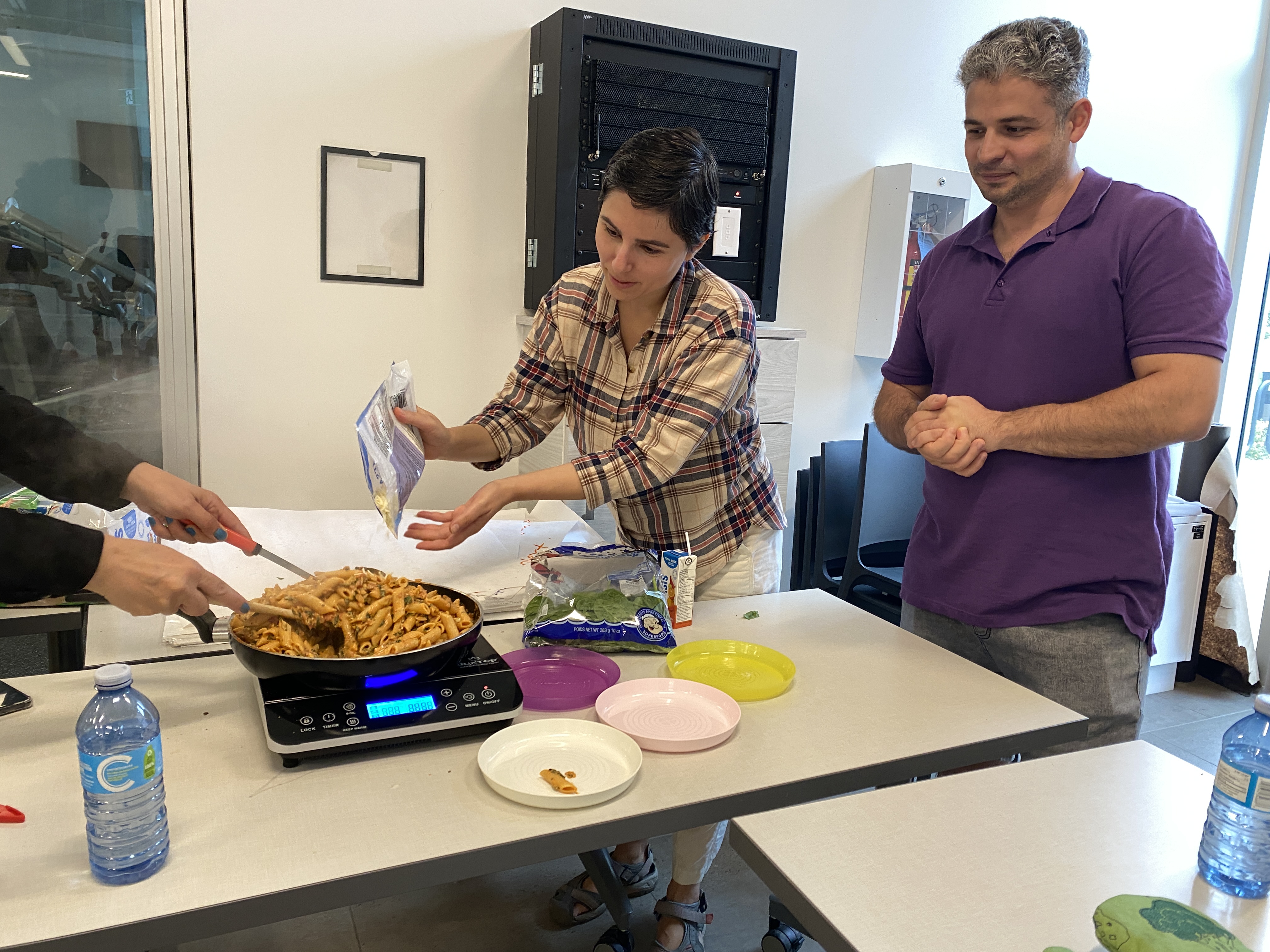

The food bank will also be maintaining a weekly free breakfast for students on campus, a free grocery bus service that takes students to off-campus supermarkets that are more difficult to transit to, and complimentary campus kitchen events that offer hands-on learning opportunities for students to learn cooking skills and recipes focused on low-cost ingredients that they can replicate at home.

“We provide all the food, and we accommodate dietary restrictions, and then people get to cook and share a meal together,” Corry said.