When you think of food banks, what comes to mind? You’re not alone if it includes third-hand stories and assumptions that may or may not be true. Food banking plays a vital role in relieving hunger and supporting communities, but misconceptions often distort the picture, cloud the conversation and contribute to stigma. Today we’re exploring five common myths you may have encountered — and setting the record straight.

Myth 1: Food bank misuse is rampant.

Food bank misuse is rare. More commonly, people visit a food bank only after having exhausted other avenues. For example, many families have maxed out their credit cards or sold off their most valuable assets by the time they reach out for support. We would actually encourage people to turn to a food bank sooner — before they lose everything or get trapped in a cycle of debt. Part of the purpose of food banks is to help everyone avoid those dire situations.

Each person faces a different set of circumstances. For instance, simply owning a vehicle doesn’t necessarily mean that someone isn’t struggling to get by. In many places, it’s virtually impossible to buy life’s essentials, access medical care and other crucial services, care for children, go to work/seek employment, or even visit the food bank without a car. (That said, Food Banks Canada’s Access Grants are helping food banks to address transportation barriers as we speak.)

Research shows that if anything, food banks are underused, not overused. According to Statistics Canada, more than 1 in 20 people in Canada are experiencing severe food insecurity. This means skipping meals, reducing food intake, or even going without food for a day or more due to a lack of money. In many cases, hungry people don’t turn to a food bank because of stigma or the impression that others need it more than they do.

You may have read in the news or in Food Banks Canada’s own reporting about food banks running low on food. This situation is very worrisome, but it’s not because of widespread misuse by people who don’t need any support. Instead, it’s because there are now millions more people living in food-insecure households, compared to the time before the pandemic. With the help of partners and donors, Canada’s food bank network is working to respond to this emergency and increase the available food supply.

Myth 2: Only people who are unemployed need food banks.

Employed people are one of the fastest-growing segments of food bank visitors. In Food Banks Canada’s latest HungerCount report, they made up approximately 19% of clients nationally.

Many people in Canada today are trying their best to get by with precarious employment. This includes around 871,000 people whose main job is in the “gig economy,” where they might be able to make ends meet sometimes but other times not.

Additionally, increases in the cost of living have outpaced wages in many parts of Canada. For example, the minimum wage in Ontario — $17.60 per hour — falls far below the living wage for Toronto, which the Ontario Living Wage Network has calculated to be around $27 per hour.

As long as that remains the case, not even stable full-time employment will necessarily be enough to protect people from food insecurity.

Myth 3: People could overcome food insecurity by budgeting their finances and planning meals.

Budgeting and meal-planning are never a bad idea, but Food Banks Canada’s research shows that for many people in Canada, these habits wouldn’t make a big enough difference to prevent food insecurity.

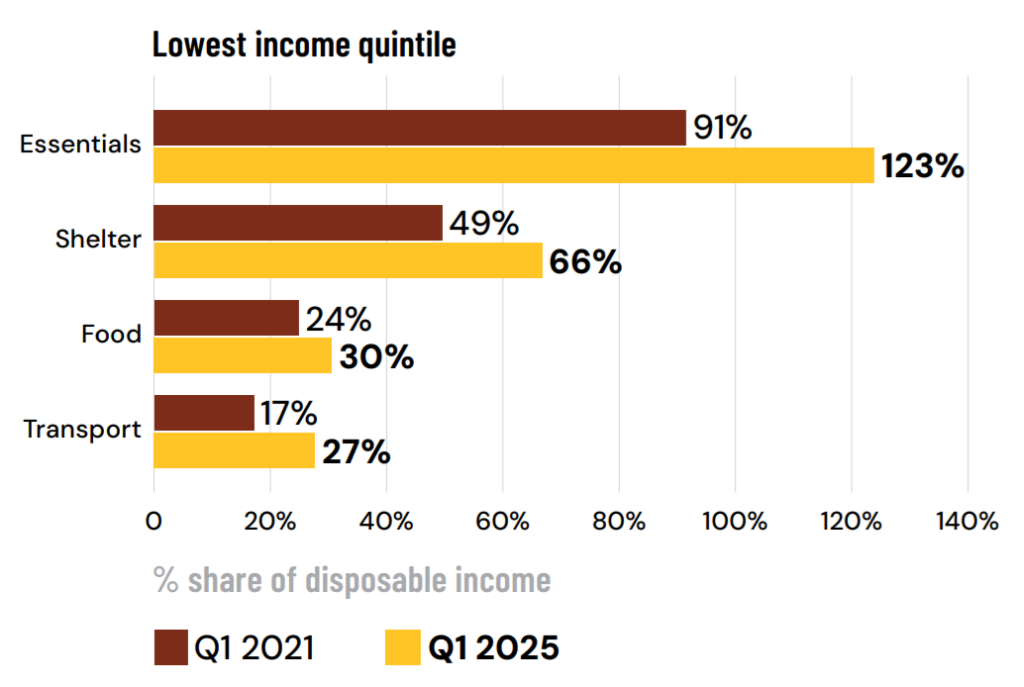

The chart below illustrates the reality facing Canada’s lowest income quintile (the fifth of people with the least income): a group with over 8 million people in it. In 2021, this group was paying nearly half of their income on shelter alone, on average, which was already very burdensome. Today, they’re paying two-thirds of their income on it, leaving just one-third for everything else, including food.

When you add up the average costs of shelter, food and transportation, the total is significantly higher than the average disposable income of this group. There’s simply no meal-planning your way out of that situation.

The middle-income quintiles, also known as the middle class, have a bit more financial flexibility compared to the lowest income quintile, but they’re still at risk of experiencing food insecurity, especially considering that many people have additional non-negotiable costs beyond food, shelter and transport. Some must manage medical issues, pay off student debts, or care for an elderly family member, for example. Once again, we must account for each person’s circumstances.

Myth 4: Food banks tend to make people dependent; they prevent them from taking steps to leave food insecurity behind.

People experience long-term food insecurity for a variety of reasons, and food banks are proud to be there for them. But intake data shows that historically, food banks have had a high turnover rate in clients.

In post-pandemic economic conditions, it’s probably more challenging than before to escape financial hardship. Even so, in a recent University of Montreal study, around two-thirds of a sample of food bank users in Quebec were no longer making regular visits after two years.

When people don’t need to worry about where the next meal will come from, it helps free up their time, energy and bandwidth for moving forward with steps such as earning credentials, getting oriented in their new country, addressing health issues or personal challenges, starting a business, and so on. And those who don’t leave financial hardship behind are still in a better position to care for themselves, their families and their communities.

In short, food banks open doors to a better future for all, because human potential is too valuable to go unfed.

Myth 5: Food banks prevent society from addressing the root causes of hunger.

Food bankers are fully aware that although providing food relieves some of the hardship caused by food insecurity, it doesn’t prevent it from arising in the first place. That’s why Food Banks Canada, provincial and territorial food banking associations and many local food banks are working together to advocate for upstream solutions.

To prevent food insecurity, all levels of government must take action. Our researchers analyze this issue and make concrete, realistic recommendations for tackling the root causes through policies and programs.

For example, the federal government recently announced that starting in 2027, the CRA will automatically file taxes for low-income Canadians with simple tax situations. These households don’t owe any taxes because their incomes are too modest. However, they’re eligible for various benefits that could make a big difference — benefits that many of them don’t currently receive because they need to file their tax returns to activate them. Barriers that can get in the way of filing taxes include a lack of knowledge about the tax system and a lack of funds to pay someone else to help navigate it.

Food Banks Canada can’t take sole credit for the government’s helpful decision, but we’ve learned that our annual Poverty Report Card was a factor in it.

That’s just one example of the systemic changes that food banks are advocating for. If every level of government does its part, we believe it would be possible to cut food insecurity in half by 2030.

In the meantime, everyone must continue to eat! Food banks and their generous supporters are committed to providing food support, even as we push for an environment where far fewer people will need it.